“I feel like I’ve been running a marathon,” says Trina Reynolds-Tyler, the data director at the Invisible Institute.

Reynolds-Tyler, along with her colleagues and reporting partners, has been on the run ever since the Chicago-based nonprofit newsroom made headlines by winning two Pulitzer Prizes and a Peabody award in early May. It’s been a whirlwind of collecting awards, doing press interviews and speaking at conferences to talk about their unique and deeply community-centric reporting process.

“I’m trying to pace myself, because I know that this isn’t going to last,” Reynolds-Tyler said about the current attention and accolades. “For me, I’m thinking about the next stage of work. When the Pulitzer was announced, I was already doing a whole other project. So, my eyes are really on what we can do next.”

The 13-person newsroom is dedicated to human rights reporting and earned their latest awards for two different projects done in partnership with other media outlets. “You Didn’t See Nothin,” a podcast series produced by the Invisible Institute in partnership with USG Audio, earned a Pulitzer and a Peabody for audio investigation and delved into a historic case of a hate crime in Chicago that left deep wounds in the community.

Reynolds-Tyler earned the local reporting Pulitzer for “Missing in Chicago,” an investigation that she co-wrote with Sarah Conway of City Bureau, another non-profit newsroom in Chicago whose founders are alums of the Invisible Institute.

The 11-part reporting project delved into police misconduct data looking for cases of police neglect and abuse related to missing Black women and girls. The reporting found mishandling of cases resulted from Chicago police not only not following procedures in missing person cases involving Black victims, but also violating the law.

The team worked directly with community members to review the data and identify descriptions that could indicate problematic cases, and then they used those guidelines to train an algorithm to identify other possible cases of abuse.

“When I came up with this idea of having community members help review the data, I knew what they’d be reviewing would contain descriptions of violence. And that could bring things up for people. So, we worked in advance to learn how we could set it up so they could have ways of processing that,” explained Reynolds-Tyler.

“Missing in Chicago” took two years to produce. It was centered around a database project, “Beneath the Surface,” developed Reynolds-Tyler in 2021 to investigate gender-based violence buried in police data. She said she’s currently working on a next stage investigation that will use the database to look at cases involving Chicago’s LGBTQIA community.

Founded with community & collaboration in mind

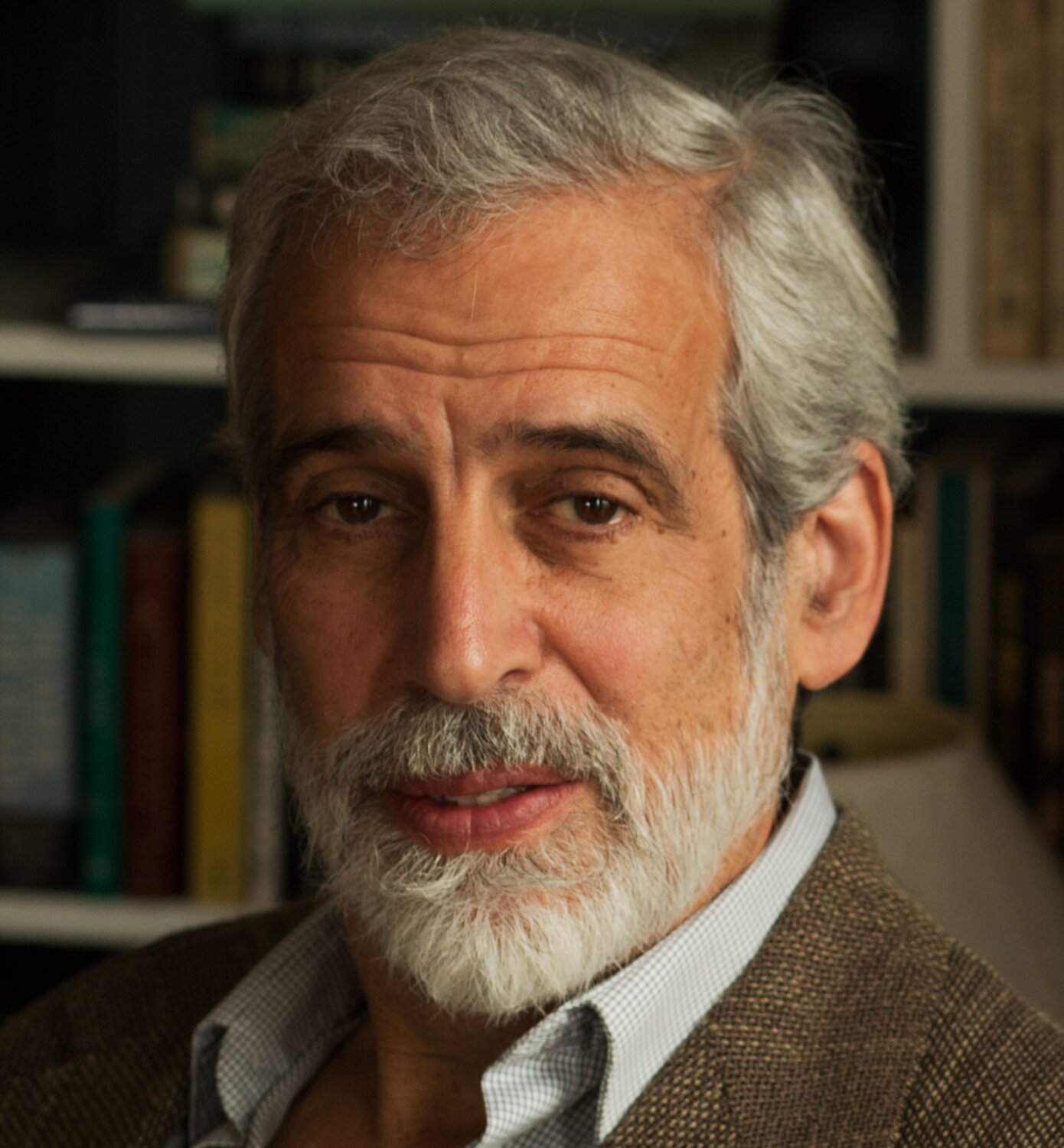

This kind of thoughtful dedication to working directly in the community is at the core of the Invisible Institute, and it stems from its founder, writer and journalist Jamie Kalven. Throughout the 1990s, Kalven worked alongside Chicago’s southside residents to elevate the issues they faced in their community, delvinig into racial injustice, neglect of public housing and police misconduct.

“To this day, I still have deep relationships from that early work that help the journalism. That has been foundational for our practice ever since,” he explained. “There are conversations that we desperately, desperately need to have in the society, and we don’t have the relationships we need to have the conversations and tell the stories and do the reporting. So, the priority is to build those relationships.”

After winning a legal battle with the City of Chicago in 2014 to publicly release troves of police data, Kalven set up the Invisible Institute as a nonprofit to make the data available to the public and to support ongoing reporting efforts. This data has been the basis of multiple reporting projects by news organizations across the city and nationwide.

“What struck me about the Invisible Institute was what it was accomplishing in practical, meaningful ways. They were both making this data available, making it available in a tool and generously helping other journalists think about using it,” said Andrew Fan, the Invisible Institute’s current executive director. “They weren't using the old school model of competitive reporting where you would normally hoard [the information]. That was inspiring.”

Fan came to the Invisible Institute in 2017 after working at City Bureau as a fellow — during a time period when both news organizations were based in the same building. The two organizations have collaborated many times over the years, as they have with many other newsrooms across Illinois and the country.

By extension, the collaborative spirit runs extra deep in Chicago. Fan explained that several news organizations in the city have a monthly meeting to talk about the public records requests they are working on and to help each other with data projects — particularly those focused on policing and human rights issues.

“Recently, there was some reporting that Injustice Watch and Block Club did about traffic stops on the West Side of Chicago,” Fan explained. “I think they just chatted with us a couple of times, which we were super thrilled about. We got to hear some of what they were identifying [and that] helped us understand some of the context for policing on the West Side.”

A different kind of institute

When Kalven founded the Invisible Institute, he said the name was a bit of an inside joke. He’d long been castigated in journalism circles — and not always welcome — for being too close to his sources. But winning the 2014 police records lawsuit and the powerful reporting by the Invisible Institute that revealed the truth about the police killing of Laquan McDonald brought about recognition.

“What's so fascinating to me now is the work that we're celebrated for — particularly work that centers the voices of the people most affected. It was almost criminalized when I started. It was just seen as so far off, so far outside the norms of journalism. So, there's been an interesting kind of narrative arc over time to the whole thing,” said Kalven.

Another way the Institute stands out is in how the organization is structured.

Andrew Fan is the current executive director, after Jamie Kalven stepped down as the Institute’s head. Kalven still serves as an adviser, and he said he sees himself as a staff person.

Fan explained that the organization works really hard to have a collaborative process internally to make decisions about editorial priorities, determine story approach and policies, including determining salary. The organizational and project budgets are available for the whole team to discuss, and they aim to have no more than a 10% variance in salaries. Fan said some exceptions for higher salaries have been allocated for staff members whose financial background and current obligations require additional support.

“I’m not going to say it’s perfect or that it’s easy to do this. We have some tough discussions sometimes,” said Fan. “But we work really hard to understand each other’s priorities and perspectives.”

The Invisible Institute publishes almost all its work in partnership with other organizations, and they don’t hue toward any specific medium. While they’ve won several awards for podcasts they’ve co-created from their reporting, they don’t want to get pigeon-holed, and Fan said they like to see where a reporting project creatively takes them before deciding on the publishing style.

The winning of the latest awards has raised some concerns. Both Fan and Kalvan talked about the pressure that can come from winning awards and the outward pressure to grow.

“I am simultaneously very proud of what we've been able to do with each other, and the truth is doing this work is never easy,” said Fan. “We want to be sure we think about what’s next, and that can be complicated. But we focus on building trust together.”

Diane Sylvester is an award-winning 30-year multimedia news veteran. She works as a reporter, editor, and newsroom strategist. She can be reached at diane.povcreative@gmail.com

Diane Sylvester is an award-winning 30-year multimedia news veteran. She works as a reporter, editor, and newsroom strategist. She can be reached at diane.povcreative@gmail.com

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here